June 1, 2016

Unit pricing hurts contractors and contracting

BY MARK BRADLEY Pricing work by the unit — per square foot, per tree, per meter — is a method as old as the landscape industry itself. Many contractors use this system as their default method for pricing work. Others are forced into it by cities, architects or project managers, who insist on getting bids in a unit-price format. But no matter why you’re doing it, recognize that unit pricing is hurting your company’s profits, not helping them.

Pricing work by the unit — per square foot, per tree, per meter — is a method as old as the landscape industry itself. Many contractors use this system as their default method for pricing work. Others are forced into it by cities, architects or project managers, who insist on getting bids in a unit-price format. But no matter why you’re doing it, recognize that unit pricing is hurting your company’s profits, not helping them. One of the most significant problems with unit pricing is that it assumes a fixed amount of labour per item. This might be 1.5 hours per tree or 0.15 hours per square foot. But that labour is just an average, and while it might help you guesstimate the time it takes to complete a job, it will more than likely hurt your profits when submitting a unit-price bid. Consider this example:

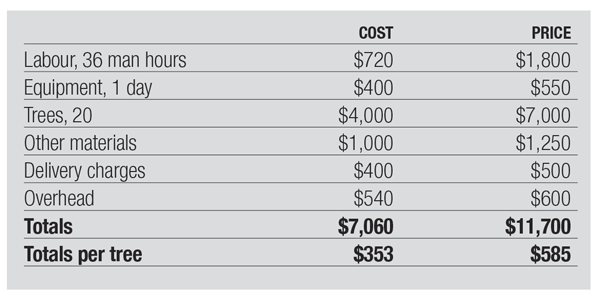

You have a job planting 20 trees; you are sending a four-man crew and figure they can plant those trees in a nine-hour day. Your estimate might look like this:

In the above example, we calculate all the costs and prices of the job and divide by the number of trees to come up with a price of $585 per tree.

We are okay here, because we calculated that $585 as accurately as possible based on the costs of the job. But watch what happens when the customer changes the bid…

Changes usually hurt the contractor

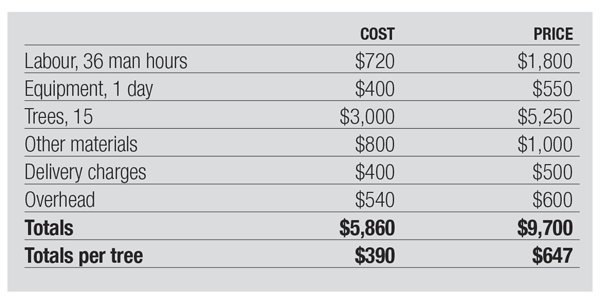

Imagine the customer says, “Thank you for your price. We’re a little bit over budget, so we only want you to install 15 trees. I’ll draw up a PO for 15 trees x $585 per tree, for a total of $8,775.” But the reality of this situation is that many of our costs don’t drop in proportion to the materials.- Our trucks need to load and leave the yard

- We need to fuel and load the trucks

- It takes the same time to drive to the site

- Our equipment still needs to be used on that site for the day

- We still need to pay the delivery charges, even if fewer materials are on board

- The crew isn’t going to clock out at 3:15 p.m. because there are a few less trees; they are likely going to stretch this job out to the end of the day

- Our overhead on this job didn’t decrease — we still have the same rent that day, and all the same time ordering and managing the work on this project

The original estimate of $585 per tree isn’t very good at 15 trees! The cost per tree increased from $353 to $390, and our price of $585 should be $647 per tree. Now our company is eating $100 per tree in increased costs and lost revenue!

Even increases can hurt

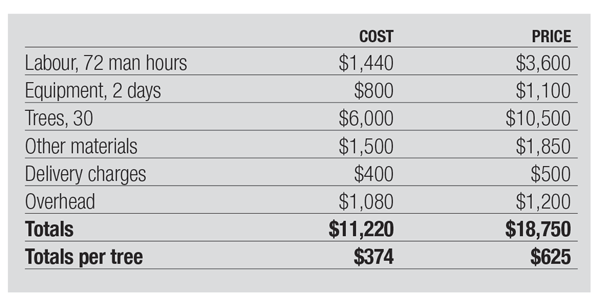

There is a good chance we can get hurt the other way, too. Let’s imagine we are low bidder at $585 per tree. They like our bid so much, they increase their budget from 20 to 30 trees.That is too many to plant in one day, so we have to send the crew back for a second day to plant the extra 10 trees. And in reality we’re not going to get to another job that day. By the time we mobilize, install the trees and break for lunch, there is not enough time left in the day to start another job.

So our bid now looks like this:

Not quite as bad as the previous example, but our increased costs and decreased revenue means we’re eating $60 per tree. On an $18,750 job, we are short $1,800.

The average price is rarely right

There are scenarios where unit pricing can work in your favour. Not every change is to the detriment of the contractor, but changes are far more likely to be the contractor’s detriment than to ourbenefit. Especially when most of these contracts are awarded on a low-bid basis. We are doing everything we can to get to the leanest price, in order to get the work. Changes are far more likely to hurt us than help us.

- Average unit prices are rarely correct, because they simply cannot factor for some very significant variables.

- Are you installing five trees or 100? You will certainly install 100 trees faster per tree, as economies of scale kick in.

- What kind of equipment is available?

- How are materials being picked up or delivered?

- What is the access to the planting location like?

- Which crew is expected to do the work?

- In which season will the work be done?

How can you fix this?

If you are pricing your own work with unit pricing, you can stop immediately. You should always use cost-based estimating using actual labour, equipment, materials, sub and overhead recovery costs when arriving at your bid. Avoid unit pricing. Not only will you have a more accurate price, you will have a clear picture about how long a job should take, equipment and materials used, and your true net profit.If you have a customer or bid that insists on this pricing method, you have little choice but to roll with the punches. But be safe. Consider the impact of changes. If possible, ask for the opportunity to re-price before you agree to changes. And at the very least, take the opportunity to educate your customer. Every job is different — and averages are almost never the right price.

Remember, using unit prices is like forecasting the average weather. The average temperature in Toronto is 9 C, but that doesn’t tell you how to dress each day. If you woke up and dressed for 9 C every day, you would rarely be dressed right for the weather!

Mark Bradley is president of TBG Landscape and LMN, based in Ontario.